Bat research and lab readiness boost Thailand’s campaign against the novel coronavirus

Thailand’s long-standing research on coronavirus strains in bats helped rapidly ramp up its capacities and curb the spread of the novel strain causing COVID-19

Thailand’s long-standing research on coronavirus strains in bats helped it to rapidly ramp up its laboratory and testing capacities and curb the spread of the novel strain that causes COVID-19, experts involved in the effort say.

A night-time curfew and lockdown of much of everyday life helped control the spread of infections, along with the continued closure of Thailand’s borders where the few people allowed to enter are carefully screened and quarantined.

But certainly, a major factor in control efforts was Thailand’s capacity to detect and manage its first cases. Thailand was the first country to confirm a COVID-19 case outside Wuhan: a passenger arriving at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport from Wuhan on 8 January. Routine screening, which was established at the airport in response to the outbreak in China, found that she had a fever.

Ministry of Public Health officials sent the woman to the Government’s Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute. There, she was diagnosed with pneumonia, and a viral infection was suspected.

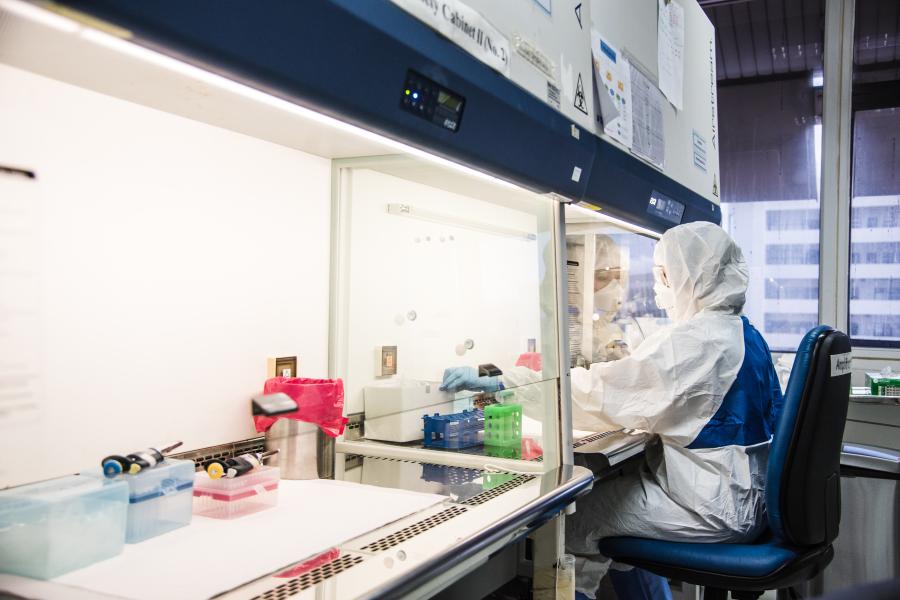

A sample, taken by swabbing the back of the nose, was analysed by the Thai Red Cross Emerging Infectious Diseases-Health Science Centre, Chulalongkorn University, which also is the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Training on Viral Zoonoses. This laboratory has expertise in coronavirus research, especially in bats.

The sample was analysed by a team led by Dr Supaporn Wacharapluesadee, the Health Science Centre’s deputy director. The team confirmed the presence of a coronavirus by a test known as real-time RT-PCR. The test, which picks up genetic material (RNA) from the coronavirus, is now routinely used as the most accurate laboratory test for novel coronavirus infections.

Dr Supaporn’s team then obtained a partial genetic sequence of this coronavirus – essentially a detailed “blueprint” of the virus’s genes -- and noted that it was remarkably similar to sequences of coronavirus strains found in horseshoe bats in China.

“We have carried out research on bats in Thailand and the diseases associated with them for more than 20 years,” said Dr Supaporn. “The distinctive features [of the novel coronavirus] did not match any others publicly available,” she said.

Following the outbreak investigation protocol, the specimen was sent to two laboratories, at the Health Science Centre and at the National Institute of Health. Both laboratories performed testing at the same time, using different methods for the most accurate results.

Dr Pilailuk Okada, the head of the National Influenza Centre at the National Institute of Health, and her team of 10 microbiologists conducted an extensive validation of the virus’s DNA using the Metagenomic Sequencing by Next-Generation platform, by referring to the dataset of publicly available whole-genome sequencing data for 30,000 base pairs.

Then, on 11 January, the full genetic sequence of the coronavirus circulating in Wuhan was released. It was compared with the full genetic sequence of the virus isolated from the Wuhan traveler that had been done by the National Influenza Centre. There was a 100% match between the viruses. Thailand successfully, and independently, confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on 13 January.

The National Institute of Health further developed the oligonucleotide primers and probes for detection of 2019-nCoV (the novel coronavirus) which were selected from regions of the virus nucleocapsid (N) gene. The panel is designed for specific detection of the 2019-nCoV (two primer/probe sets). This showed the high-standard capacities and practices of the national laboratories.

How was Thailand able to make this remarkable discovery so efficiently?

Many laboratories, such as that of Dr Supaporn, had the expertise and equipment to detect coronavirus in bats; this made it easier for them to transition to testing for COVID-19. And, in preparation for such a disease outbreak -- a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-like disease -- Thailand had already established a network of approved testing centres across the country. Thailand had adequate research capacity to quickly develop its own diagnostic kits and protocols to detect the virus.

In testing for the novel coronavirus, Thailand has been following WHO’s Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) technical guidance: Laboratory testing for 2019-nCoV, said Dr Opart Karnkawinpong, director-general of the Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health. Dr Opart said Thailand’s “One Lab One Province-24-hour reporting policy” -- having at least one laboratory in each of the country’s 77 provinces to test for the novel coronavirus -- provided timely results. This helped to quickly identify local hotspots of infection.

From 1 January to 26 June 2020, a total of 603,657 samples were tested using the RT-PCR method by laboratories under the Ministry of Public Health, and by laboratories at military and police hospitals, universities, and private hospitals.

A total of 203 laboratories in Thailand have now been certified to confirm COVID-19 test results using the RT-PCR method, said Dr Noppavan Janejai, Head of the Quality and Technical Development Department at the National Institute of Health, Department of Medical Sciences.

She said that continual laboratory exercises, simulations, modelling scenarios and risk assessments, including lessons learned from previous outbreaks such as SARS, the mosquito-borne Zika virus and a novel influenza A virus (H1N1), have helped policymakers understand the extent of the country’s staff and technology capacity. “We always need to keep our engines warm,” she said.

The Department of Medical Sciences, together with the COVID-19 laboratory network, is exceeding its daily capacity target and now processing 10,000 samples a day for Bangkok and surrounding areas and 10,000 samples a day for the provinces using the RT-PCR technique.

The 2,500 baht (US $81) cost of each RT-PCR test is covered by the budget that the Royal Thai Government has allocated to curb the outbreak and under the Universal Health Care coverage for all Thai citizens and the Social Security Fund for employees.

Accurate, rapid testing is important, but what health authorities do with the results is critical. Thanks to quick, high-quality testing throughout Thailand, public health officials are able to respond rapidly -- deploying teams to isolate patients with positive tests, and to identify people they have been in contact with, so that all can be quarantined and monitored closely. Isolating sick people and their contacts prevents person-to-person spread of the virus. It is the key to slowing, even stopping, the epidemic.

More than 1,000 epidemiological teams have been doing this contact tracing nationwide, Dr Opart said. In addition, Thailand has conducted a sentinel surveillance system that has involved close to 100,000 nasopharyngeal swab and saliva sampling tests, targeting at-risk people including health workers, detainees and inmates of jails/prisons, migrant workers, messengers, drivers.

Thailand is planning to establish a systematic and comprehensive surveillance system to be implemented over the next 14-24 months to handle future COVID-19 developments.

In spite of Thailand’s successes to date in curbing the spread of COVID-19, Dr Noppavan said she hoped that the country will remain “highly vigilant” in detecting new local transmission. Experience worldwide has shown that countries must remain vigilant and follow safety guidelines, or local outbreaks and hotspots of infection will quickly develop.

Professor Dr Steven Williams Edwards, Dr Daniel Kertesz, Dr Richard Brown, Phiangjai Boonsuk, Kanpirom Wiboonpanich contributed to this article.

Written by