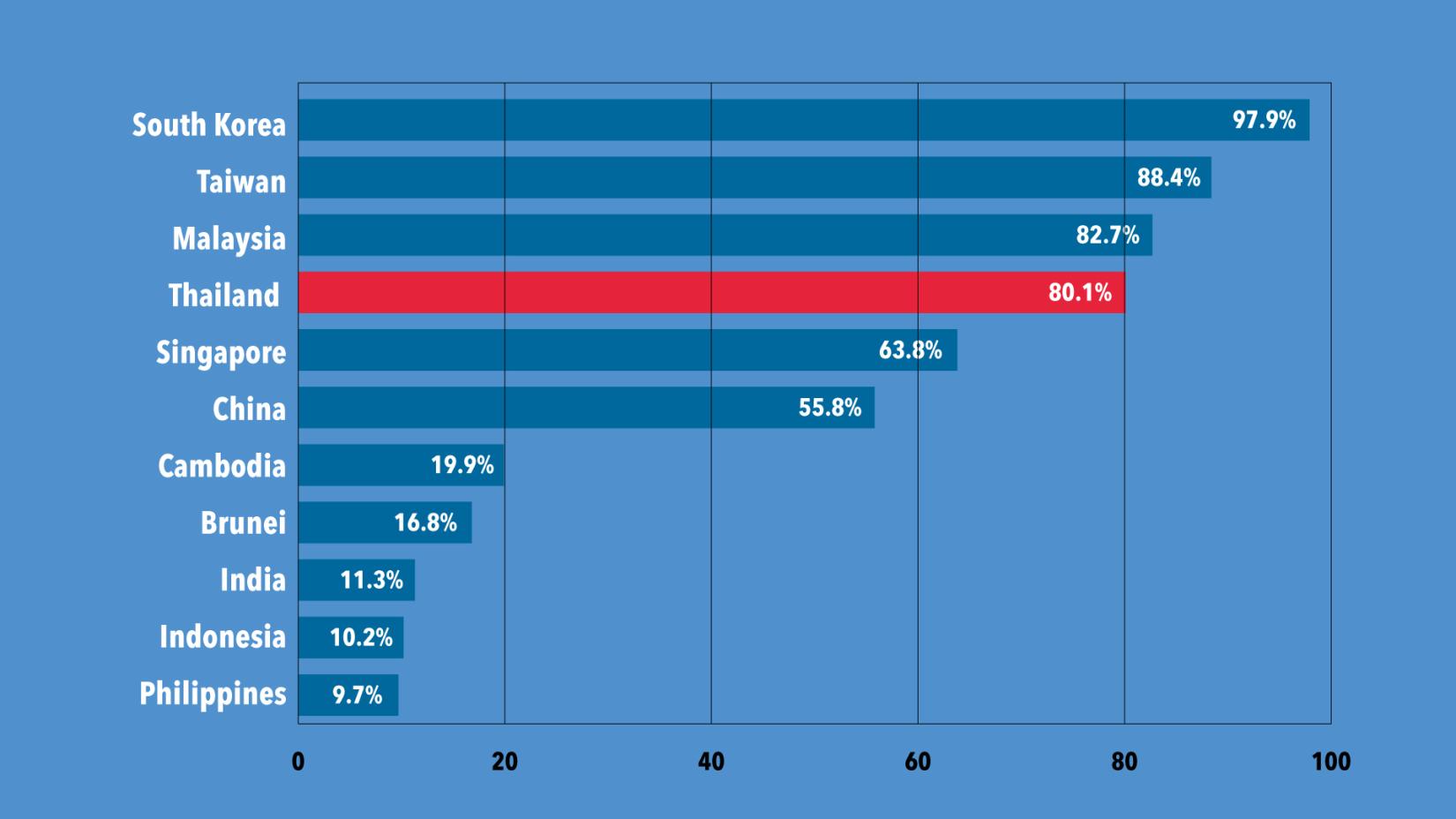

Thailand Economic Focus: Q1 household debt at 80% of GDP, highest in 4 years

05 August 2020

- Currently at 80.1% of GDP, Thailand’s household debt figure is among the highest in the region and is well above average for a country in the upper-middle income range. As a result, economic policy should adjust to having highly leveraged households in the Thai economy.

Currently at 80.1% of GDP, Thailand’s household debt figure is among the highest in the region and is well above average for a country in the upper-middle income range. Together with its meteoric rise in the past few years, household debt has been a subject of much discussion.

So why would high and rising household debt be a problem? Put simply, if households cannot pay their debt, then it increases both financial and macroeconomic instability.

- Financial stability: The rising household debt subjects both formal and informal lenders to higher exposure towards household sector. If the ability of households to service their debt is in doubt, loan losses could be significant. This will increase the fragility of the financial system.

- Macroeconomic stability: The high level of indebtedness constrains households’ access to credit and limits their ability to smooth consumption over time. This reduces the role of domestic demand as a shock absorber and increases economic volatility. It also imposes pressure on monetary policy since an interest rate hike potentially exposes households to higher delinquency probability.

As a result, economic policy should adjust to having highly leveraged households in the Thai economy. First, economic buffers need to be carefully managed. With households not being able to leverage much further, fiscal space becomes the ultimate shock absorber for the economy. This means the remaining fiscal space must be carefully managed.

Second, monetary policy should carefully consider the risks of excessive household debt accumulation arising from an unusually long period of low interest rates. Additionally, macroprudential policy measures should be implemented in order to strengthen the effectiveness of overall supervisory framework, including moving towards consolidated supervision to ensure that all providers of consumer credit services are being supervised under the same set of highly prudential standard.

Third, there is room to decrease households’ downside risks. These risks are from, for example, medical care costs on health-related issues, debt burden from deceased family members, liabilities from accidents, or damages to properties from natural disasters. One way to help is to increase access to private insurance products already existing in the market. The government should step in to help where the market is missing.

Fourth, increase households’ awareness of their own financial situation. Today’s modern technology and the popularity of smartphones can provide households with real-time information of their balance sheet to make important financial decisions. These tools should be used to help with planning and budgeting, thereby increasing financial literacy.

The author is grateful to Dr. Sweta Saxena for her support and guidance. The views expressed within this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily carry the endorsement of the United Nations. Please address all correspondences to manop.udomkerdmongkol@un.org.