Thailand’s forgotten palace

The hidden heritage gem of Phra Racha Wang Derm in Bangkok’s Thonburi district stands testament to well over two centuries of evolving relevance.

From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, the tumultuous and transitional Thonburi period (1767–82) in Thailand’s history seems to be eclipsed by both the lost splendour of ancient Ayutthaya and the palpable grandeur of the ensuing Rattanakosin period. The latter’s quintessence, embodied to this day in the sumptuous monumentality of the Grand Palace, mesmerises millions of visitors annually. Nevertheless, those momentous 15 years between the devastating fall of Ayutthaya and the founding of the Chakri dynasty were crucial for paving the way towards modern Thailand.

Away from the abiding touristic popularity of the Grand Palace, and discreetly ensconced within the headquarters of the Royal Thai Navy on the opposite bank of the Chao Phraya River, the heritage site of Phra Racha Wang Derm (literally, “former palace”) is scrupulously maintained today in a commendable effort to render this important chapter of Thai history eloquent and meaningful in a contemporary context.

Viewed from the river, the most arresting structure of the palace complex is Wichaiprasit Fort, which has been guarding the fluvial artery to the historic capital of Ayutthaya since the late seventeenth century.

In 1767, with Ayutthaya ravaged by war beyond any hope of revitalisation, King Taksin (1734–82) chose the garrison town of Thonburi as the new capital of what ultimately proved to be a short-lived kingdom. At the king’s behest, a modest palace was erected in 1768 which leveraged the strategic location of the fort.

After King Taksin was deposed in a coup and executed at Wichaiprasit Fort in 1782, prominent royals of the succeeding Chakri dynasty continued to reside at Phra Racha Wang Derm until the turn of the twentieth century, when King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) bequeathed the palace complex to the Royal Thai Navy to serve as the naval academy. Around half a century later, the navy repurposed the property into its headquarters. Today, hallowed by more than 300 years of history, Wichaiprasit Fort is the site of ceremonial gun salutes periodically held against the august backdrop of a nautical flagpole flying the flags of the navy and its commander-in-chief.

Occupying the heart of the palace complex is the late Ayutthaya architecture of the Throne Hall—the only extant edifice from King Taksin’s time—which comprises two buildings joined in a “T” configuration. As the Throne Hall has never fallen into disuse over its long existence, one can observe that certain features of its north building, such as the marble flooring and concrete pillars, evidence upgrades in the relatively recent past that did not always prioritise material authenticity. Nonetheless, the Throne Hall’s overall layout as well as the distinctly Thai-style tiered roof with three gable ends are believed to reflect the original conception from the Thonburi period. Notably, the retained open-air design of the north building provides an intriguing contrast to the typically enclosed structure of other throne halls in Thailand.

At one end of the north building is a raised platform where King Taksin would have held court. At the opposite end, one’s attention is immediately drawn to a curious bell, apparently of Chinese provenance, that the abbot of nearby Wat Hong Rattanaram (named after the wealthy Chinese man, Hong, who founded the Buddhist temple in the Ayutthaya period) gave to the navy during the reign of King Vajiravudh (Rama VI). Though the specific reason for this gift is now uncertain, legend has it that King Taksin (whose father was of Teochew Chinese origin) would take a ritual bath in the temple’s sacred pool before embarking on his military campaigns. Today, the navy’s change of command and promotion ceremonies are conducted in the north building of the Throne Hall.

The transverse south building was probably where King Taksin held private audiences. Nowadays, the navy occasionally uses the space to receive special guests and organise meetings in the uplifting presence of exquisite display models of royal barges, each of which is characterised by a distinctive design and appellation.

To the east of the Throne Hall are two Chinese-style pavilions dating from the early Rattanakosin period. Originally the accommodations for high-ranking aristocrats, the pavilions subsequently functioned as the naval academy’s storage facilities for training equipment and textbooks. Both buildings are currently dedicated to depicting the story of King Taksin through specially commissioned paintings and illuminating exhibits featuring various artefacts, including weapons from King Taksin’s time that enliven the martial theme of the smaller of the two pavilions.

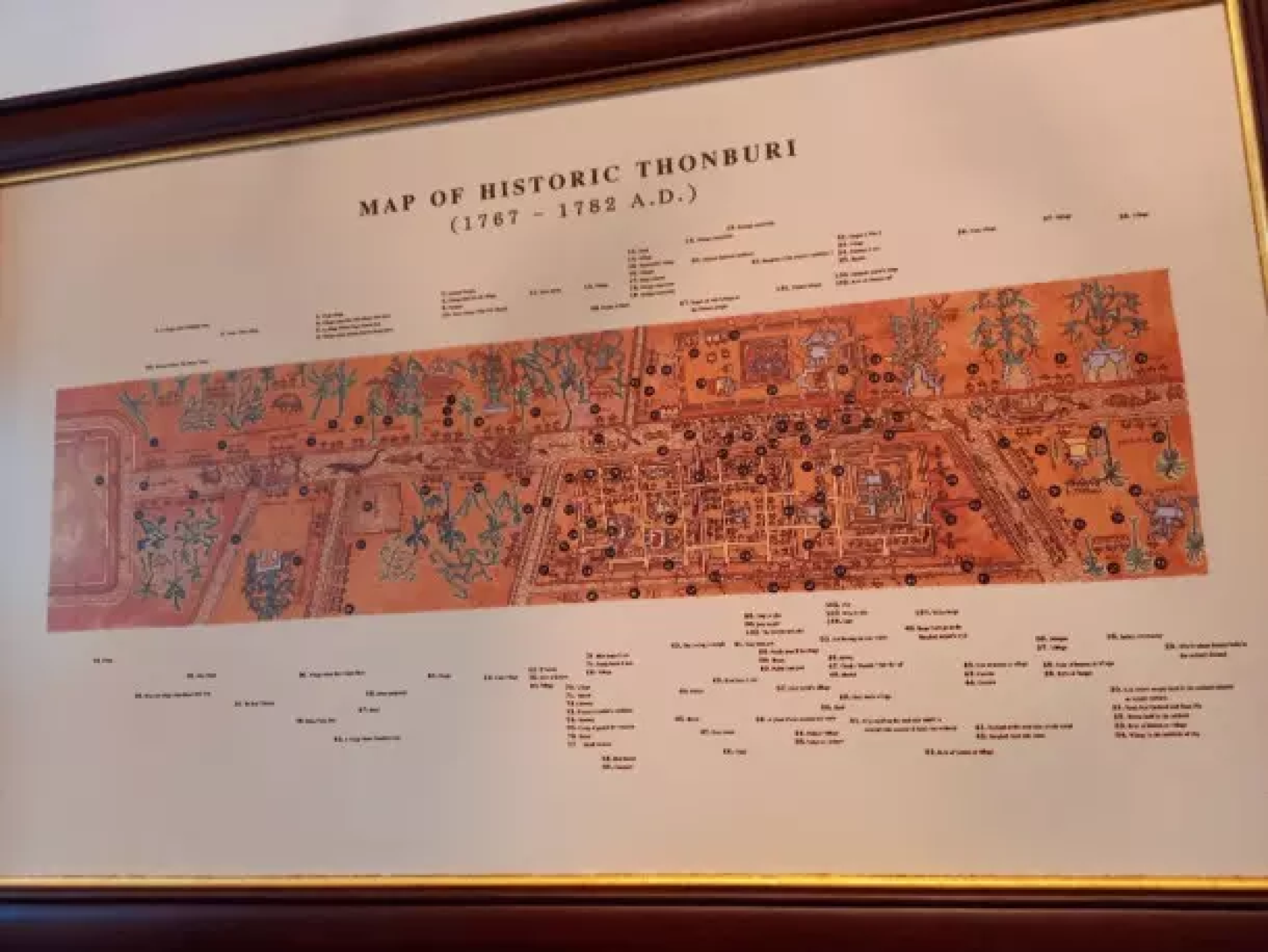

Another extraordinary artefact is a copy of a period map of Thonburi drawn up by a Burmese spy, which highlights the Thai king’s preoccupation with constructing defensive moats and walls to fortify his new capital.

As a charismatic wartime leader in whose person the warrior-king tradition was revived for the first time since the era of King Naresuan (r. 1590–1605), King Taksin is probably best known today for his military exploits. Remarkably, though, the monarch also found time for other pursuits, such as composing five narrative episodes for the Ramakien (the Thai version of the Hindu epic Ramayana), one of which is vibrantly portrayed in miniature with handmade dolls on display in the larger pavilion.

To the west of the Throne Hall is the former residence of King Pinklao, who was born at Phra Racha Wang Derm in 1808 and, in his capacity as the nation’s first naval commander from 1851 to 1865, is credited with laying the foundation for the modern Thai navy. This building is among the earliest examples of a Thai royal residence inspired by Western architecture.

Today, in addition to housing informative displays about the life and work of King Pinklao, the upper floor of the residence is enriched by precious specimens of Bencharong ware (elegantly designed porcelains historically produced in China for the Thai market). The ground floor has been converted into a compact office for the Phra Racha Wang Derm Restoration Foundation, which was established in 1995 to raise funds for, and oversee the restoration of, heritage buildings in the palace complex.

The noteworthy restoration effort at Phra Racha Wang Derm received an Award of Merit in 2004 as part of the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation, which have been recognising the successful conservation of structures, places and properties of heritage value in the region for over two decades. The award citation hails the “multifaceted and ambitious project” for the ways it “effectively incorporated the use of traditional methods and craftsmanship and conserved important examples of royal decorative fine arts.”

Far from resting on these laurels, however, Khunying Nongnuj Siridej, who initiated the restoration project nearly three decades ago and currently serves as vice president of the Phra Racha Wang Derm Restoration Foundation, remarked in a recent interview that “restoration is always work in progress.” Indeed, as is typical of riverside heritage sites in a tropical climate, issues such as soft foundations, damp conditions and termite infestation are a constant threat that can cause serious structural damage if left unaddressed. Without regular expert care and maintenance under the management of the foundation, “these buildings would be in ruins by now,” she said.

Ultimately, Khunying Nongnuj articulated her hope that the preservation of the storied structures of Phra Racha Wang Derm will help to keep history alive, tangible and resonant for future generations. After all, if history can be instructive, then perhaps the most encouraging lesson to be drawn from the Thonburi chapter of Thai history, especially for our post-pandemic world, is that the human spirit can be exceptionally resilient even in the face of unimaginable calamity. With courage and an indomitable will to survive and thrive, people learn to adapt, rebuild their lives and livelihoods, sustain their identity and culture, and cultivate life-affirming creative expression through the most turbulent of times.