Thailand Economic Focus: Demographic change in Thailand: How planners can prepare for the future

19 ตุลาคม 2020

With age comes wisdom. But collective wisdom in an aging society can be disruptive from an economic point of view.

With age comes wisdom. But collective wisdom in an aging society can be disruptive from an economic point of view. An aging society means fewer working people to support a larger base of older people. This leads to a shortage of qualified workers, making it more difficult for businesses to fill in-demand roles. An economy that cannot fill in-demand occupations faces adverse consequences, including declining productivity, higher labour costs, delayed business expansion and reduced international competitiveness. In some instances, a supply shortage may push up wages, thereby causing wage inflation and creating a vicious cycle of wage and price spiral.

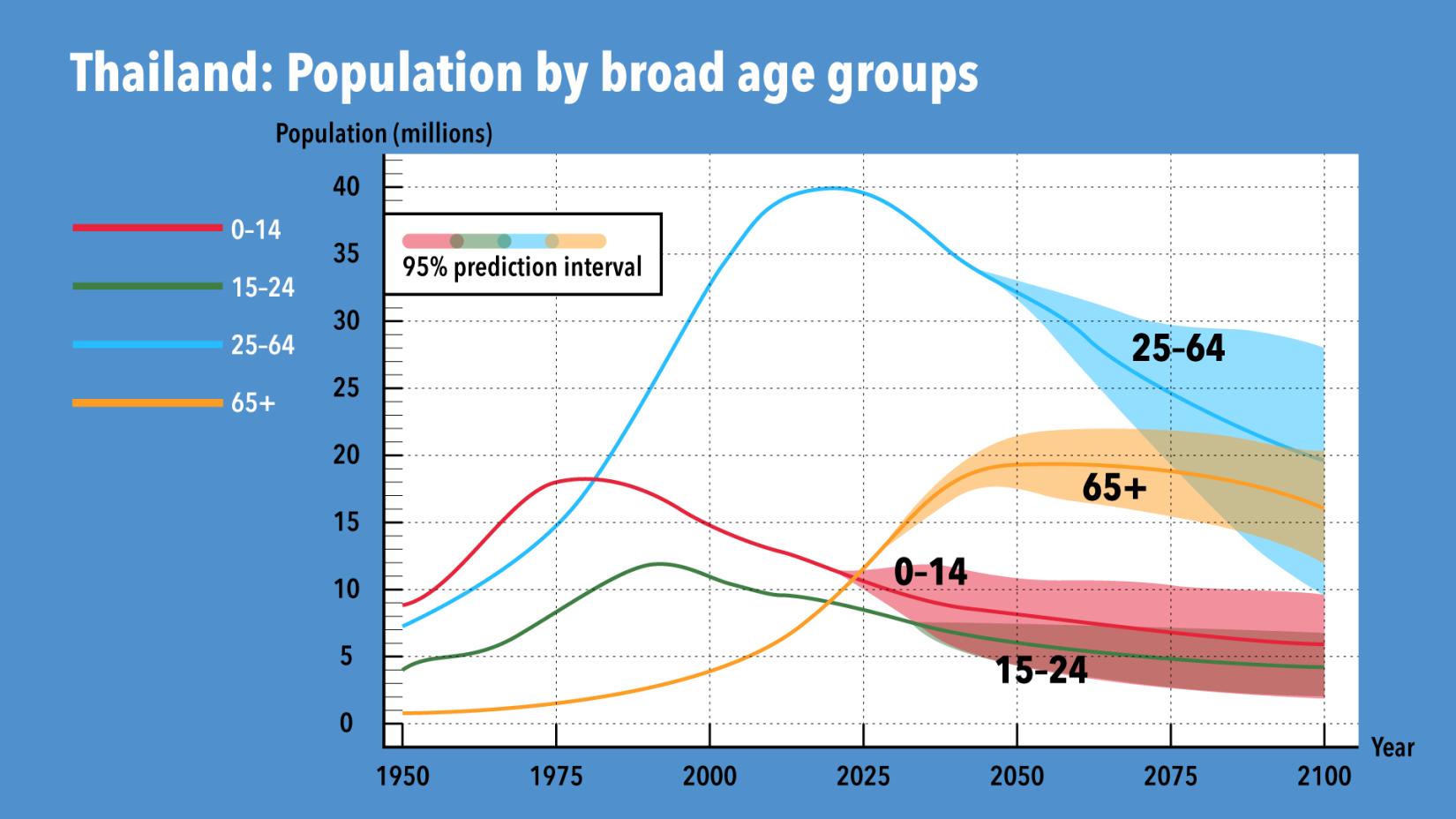

Thailand is about to experience such a demographic change. According to the United Nation’s World Population Prospects 2019, the number of senior citizens will more than double from 9.0 million people or 13.0 percent of the total population in 2020 to 19.5 million people or 29.6 percent of the total population in 2050. This means that out of every three Thais, one will be a senior citizen.

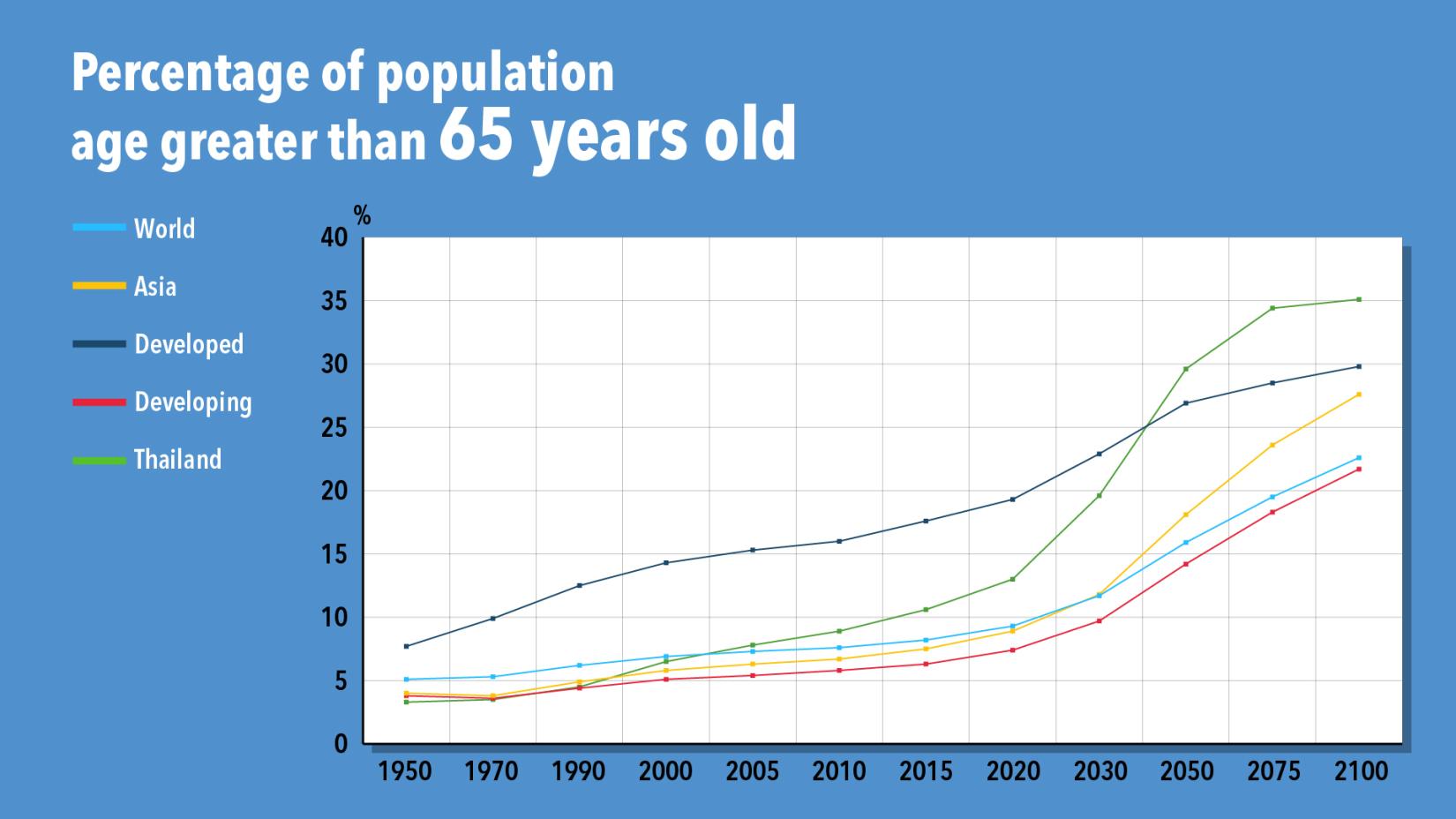

However, Thailand is not alone. The UN forecasts that all regions around the world are on the aging trend with the developed countries facing the most severe problem with the share of population older than 65 years old to rise to around 26.9 percent by the year 2050. Yet, the share of older population in Thailand will be much higher in the next 30 years, compared to the world and Asia (excluding Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong and Korea)

Thailand’s rapid aging is particularly striking—and worrisome—for its income level. The median age in the population has increased rapidly to about 40. While lower than the current median age in Korea and Singapore, the latter two economies reached a similar median age at much, much higher levels of per capita income. Thailand is running out of workers at a time when the country has not yet acquired the skills, capital, and technology to really increase their productivity.

The aging has been driven largely by Thailand’s very low fertility. The total fertility rate, defined as the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime, in Thailand may drop from 1.53 (2015-2020) to only around 1.42 (2025-2030), closer to rich countries like Japan and Singapore and lower than comparators such as Malaysia. As a result, the number of children will cross with the number of older persons in 2025, reflecting the rapid decline in fertility that began in the mid-1980s in Thailand.

As population ages, growth in the working age population will drop off sharply. Economic growth often reflects demographics. Countries with a rapidly growing work force typically experience rapid economic growth, a phenomenon known as the demographic dividend[1]. In Thailand, however, the working-age population will witness a downward trend, from 43.2 million in 2020 to 36.5 million in 2040. Meanwhile, the ratio of working-age to senior people is expected to drop from 3.6 in 2020 to 1.8 in 2040, according to the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC).

Even so, the same demographic conditions that are producing an end to the demographic dividend may yield the longevity dividend[2].

Whether increased longevity is a burden or a dividend depends on the extent to which societies prepare for the challenges of ageing populations and plan for making use of the benefits. One of the most tangible benefits of living and working longer is the retention of skills and knowledge. Older workers have formal and technical skills which they have accumulated through long service. Employers in sectors which are facing labour shortages are seeking to acquire such skills through programmes such as mid-career apprenticeships. Older workers can also help younger ones find pathways into secure and well-paid work through mentoring and job sharing. Many older people are contributing to social welfare by taking on caring roles such as looking after grandchildren and elderly parents.

The longevity dividend, like most economic benefits, is attainable but needs to be worked for. Mobilising older workers’ experience, knowledge and skills will mean that rising life expectancy can be both socially and economically good.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sweta Saxena for her editorial comments. The views expressed within this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily carry the endorsement of the UN. Please address all correspondences to manop.udomkerdmongkol@un.org.

[1] This would be the case if proper investments are in place to create decent jobs and employment for young people with well-balanced gender equality.

[2] The longevity dividend is characterized by an accumulation of wealth and savings as older individuals save for consumption at old age and invest in their human capital, especially in health and education.